Salinger

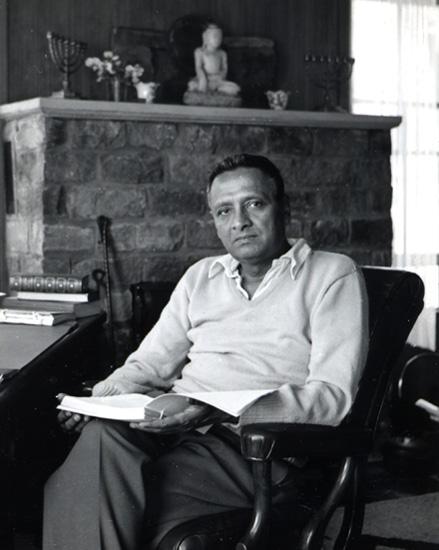

Salinger's spiritual teacher, Swami Nikhilananda, in his study at Thousand Island Park

J.D. Salinger and Vedanta

Salinger's source of spiritual inspiration that fueled so much of his work

How many times have you read a book, a poem, or a story that seemed to speak directly to you, that uplifted you or inspired you to grow? And how many times did you wonder, after reading that book or story, if the author had actually intended to say what you had perceived, or whether you were simply misinterpreting the text in order to match your own personal needs? Author intent matters. It matters to readers. It matters to those of us who love literature. The messages a writer seeks to present through his work are important to those who find strength in the words. A writer can deliver information, humor, and wit. But the greatest gift an author can give is to comfort us with the assurance that we are not alone.

How many times have you read a book, a poem, or a story that seemed to speak directly to you, that uplifted you or inspired you to grow? And how many times did you wonder, after reading that book or story, if the author had actually intended to say what you had perceived, or whether you were simply misinterpreting the text in order to match your own personal needs? Author intent matters. It matters to readers. It matters to those of us who love literature. The messages a writer seeks to present through his work are important to those who find strength in the words. A writer can deliver information, humor, and wit. But the greatest gift an author can give is to comfort us with the assurance that we are not alone.

I'd like to speak as an average reader, a reader who has asked this very question many times in my life. But I've never asked the question more often or with more urgency than when it came to the writings of J.D. Salinger.

The Source of Inspiration

Salinger's stories spoke to me on a personal level and seemed to resonate with spiritual messages that inspired and gave me comfort. He had not produced a deep resource of literature: just four thin books, a single novella, and twenty-one very slim short stories. Yet, within the accessible and often humorous prose of this brief output, I sensed something large brimming just beneath the surface: gentle messages exposing fundamental issues about the meaning of life, exploring the nature of humanity and the existence of God. So, I came to understand Salinger's stories as steps along the path of a spiritual journey. But I wondered about the source of that inspiration.

I am far from alone with that perception. Over the years millions of average readers have sensed a spiritual underpinning to Salinger's works that have inspired and even enlightened them. And just like me, many wondered whether the author was trying to convey a deliberate spiritual message—and what that message might be. It was a question with no obvious answer. Rumors of Salinger's personal life suggested a revolving door of religious positions; and his stories seemed to present any number of beliefs. He prefaced his Nine Stories collection with a Zen koan—so, many figured him to be Buddhist. His story “De Daumier-Smith's Blue Period” centered on a nun, so perhaps he was Roman Catholic. But his book Franny and Zooey explored the Russian Orthodox Jesus Prayer, so maybe he was an Orthodox Christian. And what about his later works? His final book offered a Taoist tale but quoted liberally from the Indian holy man Sri Ramakrishna; and his last publication contained a long homage to Swami Vivekananda, who had brought Vedanta to the West. It all seemed like a confusing smorgasbord of doctrines, especially when coming from the grandson of a rabbi.

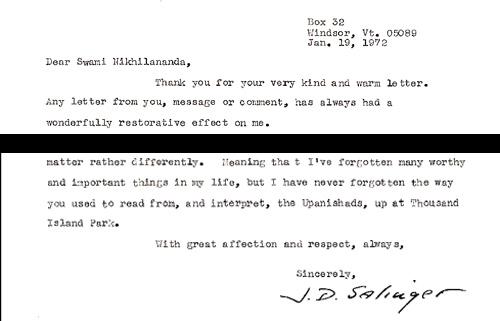

Tonight we celebrate the donation of an important cache of Salinger correspondence by the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center of New York to the Morgan Library & Museum. The centerpiece of the collection are letters written by Salinger between 1967 and 1975 to Swami Nikhilananda and Swami Adiswarinanda, spiritual leaders of the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center; but it is important to note that Salinger continued to correspond with the Center through 1996—representing an unbroken relationship that spanned 45 years—and that, according to his widow, Colleen, Salinger drew great strength from the Center's continuous mailings and monthly devotional bulletin until his death in 2010. So, making these documents public will go far in adding balance to the popular perception of Salinger's life by spotlighting the intensely spiritual side of his complex character, and perhaps even more importantly, encourage readers to re-examine the author's writings with fresh eyes. In light of the commonly held belief that Salinger flew from one religious conviction to another, this material evidence of his consistent respect for Vedanta is like lowering a drawbridge that connects us, as readers, to the spiritual foundation Salinger deliberately imbedded into so much of his work. They help us to slice past many interpretations of Salinger's writings that ignore or otherwise sideline the influence of Vedanta, and help to reveal the spiritual messages so often avoided by critics and academics--but instinctively perceived by readers.

Introduced to Vedanta

For those unfamiliar with Vedanta, it is an ancient belief system that first originated in India and was reinvigorated in modern times by the Bengali holy man Sri Ramakrishna. Vedanta was introduced to the West in 1893 by Ramakrishna's principal disciple, Swami Vivekananda. Vivekananda spent three years traveling throughout the United States spreading the idea of the harmony of religions—the conviction that all faiths that lead to a realization of God are equal and valid—and teaching the concept of the four yogas—paths by which individuals can obtain a closer union with God. Both of these teachings had a profound effect upon Salinger and made deep inroads into his work.

Salinger was introduced to Vedanta just as he was putting the finishing touches on The Catcher in the Rye . By 1951, he was regularly attending services and lectures at the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center—a mere two blocks from the Park Avenue apartment in which he had been raised--and studying under Swami Nikhilananda, whom he embraced as his spiritual teacher. Nikhilananda was himself an accomplished author and Salinger eagerly studied his writings. Several of the letters being donated tonight acknowledge Salinger's esteem for Nikhilananda's works. But none of the swami's publications seems to have resonated with Salinger more than Nikhilananda's translation of The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, the literary paragon of Vedantic faith. Salinger was electrified by the book's contents, a collection of the sage's teachings and conversations. That December, he wrote with a convert's zeal to his British publisher about the text, extolling it as “the greatest religious book of the century”. It was an enthusiasm that would stay with Salinger, and one that he would pass on to his fictional characters.

When Salinger adopted Nikhilananda as his personal teacher, he knew he was taking a major lifetime step. Nikhilananda was no ecclesiastical Santa Claus. He was a formidable presence, tall and robust, and exuded a determined energy. And he drove the message home without compromise. Born in 1895 to a middle-class family in present-day Bangladesh, after studying journalism at the University of Calcutta, Nikhilananda fought against colonial rule in India and was imprisoned by the British for insurrection. But after absorbing the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna, he joined the Ramakrishna Order—and received spiritual instruction [initiation] from Sri Sarada Devi, the wife and spiritual companion of Ramakrishna himself. In 1931, the Order sent Nikhilananda to the United States where in 1933 he founded the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center on Manhattan 's Upper East Side.

Vivekananda Cottage, Thousand Island Park

But it was another location sacred to Vedanta that had a major effect upon Salinger and solidified his relationship with Nikhilananda. On Wellesley Island in the Saint Lawrence River is the small, idyllic, community of Thousand Island Park . It was there that Swami Vivekananda stayed for seven weeks in 1895 in an ornate Victorian cottage nestled in the woods. Within his upstairs room Vivekananda wrote and meditated and enjoyed what he considered to be his most productive time outside of India.

In 1947, Nikhilananda determined to purchase the cottage, which had suffered from decades of neglect, and after an arduous renovation to its former glory, christened it Vivekananda Cottage, the spiritual retreat of New York 's Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center. In a short time, members of the Center could be seen occupying the cottage during the summer months, and daily vespers could be heard wafting from Vivekananda's upstairs room. Seminars were held within the cottage and Nikhilananda could be overheard reading to groups of followers from the Upanishads and The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna.

Salinger is on record for having attended Nikhilananda's summer seminars at Thousand Island Park in July, 1952, and again the following year. There, he attended lectures and meditated in the sanctuary of the upstairs room of Vivekananda Cottage.

By Salinger's own assessment his experience there was transcendent. He recalled it with reverence and the effect seems to have been one of creative as well as spiritual inspiration. It is no coincidence that almost immediately upon leaving Thousand Island Park, Salinger left New York in search of his own home and purchased a tract of hillside property in rural New Hampshire—complete with a disheveled cottage set in the woods: a near-perfect New Hampshire version of Vivekananda Cottage and grounds.

The same year that Salinger moved to New Hampshire he began to present the teachings of Vedanta through his fiction. In order to convey his message, he created the fictional Glass characters, a family of spiritual-seekers who populated every book and story he wrote after 1953.That message intensified with each succeeding work, consuming the 1961 blockbuster Franny and Zooey and continuing in Salinger's fourth book, Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour-An Introduction. In 1965, Salinger produced his final publication, a story printed in The New Yorker titled “Hapworth 16, 1924”. It was in “Hapworth” that Salinger delivered a direct tribute to Vivekananda and perhaps his clearest declaration of Vedanta.

The Ideas of Vedanta

Salinger's Glass family characters were deliberately crafted to resemble his readership—who were modern, American, and largely urban—in order to reach his audience with Eastern philosophies they might distrust coming from characters less familiar. Salinger explained as much to Nikhilananda in 1961, when he presented the swami with an inscribed copy of Franny and Zooey, the most successful book Salinger ever published apart from The Catcher in the Rye.

Now, Sri Ramakrishna had stressed the importance of humility and warned his followers against embracing the fruits of their labor, instructing them to return those benefits back to God. But Salinger assured Nikhilananda that he had written the book—not to amass fame or fortune— but “to circulate the ideas of Vedanta”.

That was a slippery tightrope to navigate. In order to “circulate the ideas of Vedanta” to as wide an audience as possible, it was vital that Salinger's books become as successful as possible. But such success inevitably brought with it an assortment of spiritual poisons: material wealth, celebrity, and the temptation of ego. Even at Thousand Island Park , the fruits of Salinger's successes were inescapable. Small groups of young girls would follow the author as he climbed the hill from his bungalow in town up to Vivekananda Cottage, each clutching a copy of The Catcher in the Rye and trying to muster the courage to approach Salinger for an autograph.

To some, Salinger's claim might seem odd on another level. More than any book he wrote, Franny and Zooey relies upon a steady stream of Christian references. But once we recognize that the harmony of religions is a cornerstone of Vedanta, the variety of different religious references in Salinger's stories begins to make sense. Of course, not all religious doctrines are in agreement with Vedanta. But those that are not are conspicuously absent from his works. Every religious allusion Salinger used, from the Taoist tale in Carpenters , to the Zen koans in Seymour-An Introduction, or even the nuns in The Catcher in the Rye, are presented in careful concert with the teachings of Vedanta.

But perhaps the single teaching of Vedanta that most informed Salinger's work—and possibly most affected his life—is the Vedantic concept of karma yoga. Karma yoga teaches that everything in life—from one's vocation to the smallest daily duty—can be approached as an act of service, accomplished as a prayer, as a meditation, and can lead to a clearer realization of God. Salinger readily embraced the concept of karma yoga as an interpretation of his own craft. In short, he came to believe that his own work – his writings – were potentially holy and he learned to regard his work as a path to unity with God if approached and executed with humility.

And much of his work conveys the message of karma yoga. His characters struggle to encounter it, to perform it and perfect it. When Franny seeks to fulfill the Biblical exhortation to “pray without ceasing” in Franny and Zooey , she is seeking out karma yoga. When Zooey encourages her to be God's actress, he is urging karma yoga. When he repeats his brother's parable of “The Fat Lady” and shines his shoes for Christ Himself, he is recognizing karma yoga. When Seymour Glass, in Salinger's final publication, gives his life over to the service of God, he is practicing karma yoga.

But Salinger's embrace of karma yoga inevitably clashed with the materialism and egotism necessary to publishing and promoting his books in modern America; and he eventually resolved that the fame his literary successes delivered—the vulgar fruits of his labor-- were more spiritual quicksand than service.

So Salinger abandoned publishing after 1965, completing a gradual retreat into a private life of relative simplicity. Still, he never ceased considering himself a working writer. Likewise, long after his withdrawal from the public arena, his bond with Nikhilananda remained strong. Foremost, he respected the swami as a spiritual teacher, the man whose translation of The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna had allowed him to experience the teachings of Vedanta and whose personal interpretation of those teachings had brought them home. Secondly, Salinger could not help but be impressed by the swami's countenance and personal history, which gifted him with an authority that gave his opinions an extraordinary weight. Nikhilananda, in short, had dived headlong into his work, and Salinger, who had done his own share of heavy lifting, certainly respected that. But perhaps equally vital to the bond between them was the swami's earned status as an author, as a man of scholarship and letters, a position that doubtless accorded Salinger's impression that the swami was something of a kindred spirit who shared and therefore understood his own calling. It allowed for a closeness and ease between the two men that transcended an ordinary relationship between a spiritual teacher and his pupil.

The Letters

Letters sent by Salinger to the swami reveal an ongoing relationship of mutual admiration and trust. Their correspondence covered not only spiritual topics but also personal subjects including information on well-being of Salinger's family, discussions on health, current events, and the status of each other's work. Salinger queried the swami's stance on the benefits of holistic medicine, and Nikhilananda turned to Salinger for thoughts regarding his own writings, which Salinger enthusiastically endorsed. Moreover, author and teacher provided each other comfort in times of need. In the opening years of the 1970s, Nikhilananda's health began to fail and he found himself dependent upon a wheelchair. Feeling discouraged that he could no longer perform his duties as robustly as he had in years past, Nikhilananda confided his concerns to Salinger, lamenting that he could do little more in his present condition than read from the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna to small groups of devotees. “I imagine the students who are lucky enough to hear you read from the Gospel would put the matter rather differently,” Salinger pointed out. He then reminded the swami of their time together at Vivekananda Cottage. “I've forgotten many worthy and important things in my life,” Salinger confessed, “but I have never forgotten the way you used to read from, and interpret, the Upanishads, up at Thousand Island Park.”

Nikhilananda passed away in 1973, less than two years after Salinger delivered his words of comfort. He had been leader of the New York center since its inception forty years before and Salinger's friend and mentor for more than twenty. Salinger traveled to New York to visit the Center and after being recognized by a young attendant while obtaining incense, was introduced to Swami Adiswarinanda, who had succeeded Nikhilananda as the Center's spiritual leader. To a large extent, Salinger established a rapport with Adiswarinanda similar to what he had enjoyed with Nikhilananda. But Salinger's correspondence makes it clear that the author sorely missed his longtime friend and that his reverence for Nikhilananda remained strong and at the forefront of his mind. He remembered the swami to Adiswarinanda as someone who possessed “inspired intelligence, devotion, and authority” and spoke of him longingly.

For his part, Adiswarinanda counseled Salinger at pivotal times in his life: after the death of Salinger's parents, and not long after the author's break-up with Joyce Maynard, an aspiring young writer thirty-four years Salinger's junior. One suspects that Salinger may have blamed his own spiritual weakness for allowing the relationship with Maynard. In frustration, he confided to the swami that he was dissatisfied with his spiritual progress. In analogy, he quoted lines from an ancient Sanskrit poem that had been recommended to him by Nikhilananda years before:

“‘In the forest-tract of sense pleasures there prowls a huge tiger called the mind. Let good people who have a longing for liberation never go there.' I suspect that nothing is truer than that,” Salinger added, “and yet I allow myself to be mauled by that old tiger almost every wakeful minute of my life”.

Salinger's Hope

These are just a few background references that help make the letters we recognize tonight so fascinating. But they are more than mere correspondence between an author and his spiritual teachers. They are an affirmation, a reassurance to readers worldwide who have intuitively sensed the spiritual essence contained within Salinger's works and who have wondered, just as I had wondered, whether that spirituality was a deliberate contribution imbedded by the author or something imagined by the reader. Salinger's letters to the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center help to solve that mystery in a material way. Everything Salinger wrote after, and perhaps including, The Catcher in the Rye was clearly influenced by Vedanta and offered to the public as solace to what Salinger recognized to be a spiritually aching world.

But I can't stand here and properly dissect Salinger's writings to expose every instance of Vedanta within them – the Vedanta that holds them together and that speaks to our hearts as readers. Only you can do that. Vedanta is a faith that embraces every path to oneness with God regardless of the label: Hindu, Buddhist, Jewish, or Christian. It is a doctrine of inclusion that melded perfectly with Salinger's writing philosophy. Salinger's highest hope was that his efforts would bring his readers – not to Nirvana or to Heaven – but to the place of self-examination. That's why the best of his works are so open-ended, so given to individual interpretation, and so powerful. Vedanta was certainly Salinger's personal inspiration. The letters we are sharing tonight help to establish that. And being so inspired, he could not avoid sharing that inspiration with the world. But Nikhilananda had taught his student well. It was not the label that mattered. It was the effect upon the soul. J.D. Salinger was not a missionary or a monk. He was an author. And he was an author of fiction. This was the gift that God had given him, and he served that gift – and God through it – by carefully balancing his vocation with a gentle, but clear, affirmation of faith.