The Glass Family Series

Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters

and Seymour — An Introduction

a sort of prose home movie

Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour-An Introduction is the title of Salinger's fourth and final book, It was released on January 28 1963 by his usual publisher, Little, Brown and Company. Like its predecessor, Franny and Zooey, Raise High and Seymour compiles two stories previously published in The New Yorker. The book's critical reception was more subdued than the reaction to Franny and Zooey, but reviewers still condemned its religious content as well as the seemingly erratic writing style of “ Seymour-An Introduction.” Yet once again, readers defied critical advice and flocked to the book. As a result, Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour-An Introduction was the third bestselling book of 1963. The collection is as controversial today as it was upon its first publication and consequently just as intriguing to readers.

“Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters”

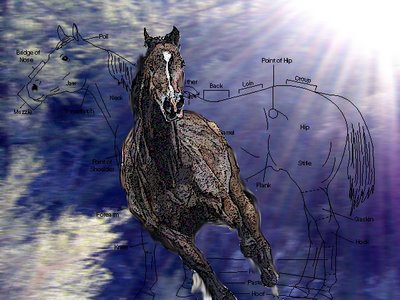

The collection's first installment, “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters” opens with the sublime parable of a simple vegetable hawker assigned the lofty task of selecting the perfect steed for a demanding Chinese duke. The tale imbeds the story that follows with underlying significance and reintroduces readers to some of the story's characters, Seymour Glass, his brother Buddy and sister Franny.

The story itself is Buddy Glass' recount of the events of Seymour's wedding day, and although Seymour himself never actually appears in the story, his character dominates each of its pages.

“Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters” offers a light and comfortable read that shifts between humor and intensity. It has often been acclaimed as Salinger's most masterful character study and perhaps his most technically perfect production – at least in the conventional sense.

“Seymour - An Introduction”

In contrast to “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” the collection's second and lengthier contribution, “Seymour-An Introduction,” refuses to conform to literary standards. Its erratic stream-of-consciousness construction has been percieved by different readers as being either the story's charm or its downfall. While almost a half century has passed since it's first appearance, the story remains just as controversial today as it was in 1959.

It is near impossible to give a linear synopsis of “Seymour-An Introduction.” Ostensibly, it is a very personal account of an author writing a story as Buddy Glass painfully (and joyously) attempts the relay the life and personality of his brother Seymour years after Seymour's suicide. But the result of memory entraps Buddy in the pain of his brother's absence and it is only through a long series of koan-like reminiscences – each self-contained parables that deliver a spiritual message – that Buddy finally come to terms with Seymour's death and the very world around him.

“ Seymour-An Introduction” actually plays out multiple stories simultaneously. In this piece, J.D. Salinger is completely imbedded within the character of Buddy Glass and many have interpreted the story as being an autobiographical work. It is also a biographical sketch of Seymour Glass as well as that of his brother, Buddy. Which character is actually dominant in the story, Buddy, Seymour, or Salinger himself, is a question still debated. However interpreted, like each installment of the Glass family series, the novella remains primarily a spiritual account (a fact that Salinger clearly states within its opening pages) and it presents Seymour Glass to the world as having been the first true saint (in a new, modern-day sense) to have lived in urban American society.

"Seymour - An Introduction” Preface

The actors by their presence always convince me, to my horror, that most of what I've written about them until now is false. It is false because I write about them with steadfast love (even now, while I write it down, this, too, becomes false) but varying ability, and this varying ability does not hit off the real actors loudly and correctly but loses itself dully in this love that will never be satisfied with the ability and therefore thinks it is protecting the actors by preventing this ability from exercising itself.

It is (to describe it figuratively) as if an author were to make a slip of the pen, and as if this clerical error became conscious of being such. Perhaps this was no error but in a far higher sense was an essential part of the whole exposition. It is, then, as if this clerical error were to revolt against the author, out of hatred for Iron, were to forbid him to correct it, and were to say, 'No, I will not be erased, I will stand as a witness against thee, that thou art a very poor writer.'